Changing Course

2025-04-01T05:00:00Z

At the time, Freilich was an undergraduate majoring in paralegal studies at Roger Williams University and thought that maybe someday he'd go to law school. But the allure of free travel and his extroverted nature made working for an airline feel like a natural step away from that path.

While serving as a store manager for a Starbucks in Bristol, Rhode Island, one of Mackenzie Freilich's direct reports was also working as an airline flight attendant.

"Sports always will be a huge part of my life," she says, “but I want to be able to have a career that I can help people solve problems.”

After law school, she hopes to combine athletics and property management with law.

"They allowed me to take it at 6 or 7 p.m. instead, so I [still had a good shot] at doing well on the exam and not being dead asleep," she says.

The familiar flexibility of online classes suits her. During final exams in 2023, she was competing in Finland, and the test was scheduled for the middle of the night in Scandinavia.

Typically, her days are filled with school and training, but she is currently focused on recovering from a cervical disc herniation she suffered in February. "Of course, I eat and sleep sometimes in there as well," she adds.

Her mother discovered St. Mary's online program in 2022, and Vinecki applied. "It was just so neat because I'd been used to doing online schooling for years and years," she says.

"There's no way I could do in-person law school while still professionally skiing," she says. "I'm traveling many times for two months on end–sometimes more–throughout the winter."

At the University of Utah, Vinecki studied business administration, taking a mix of in-person and online classes while continuing to balance the demands of the U.S. Ski Team. A business law class "was right up my alley," she says, offering practical skills helpful for handling her real estate rental business and her sponsorship contracts. That sparked her interest in law school. But when she graduated in 2021, no accredited law schools offered fully online programs.

In the eighth grade, she moved away from her mom and brothers to Utah to train full time on the Fly Freestyle elite development team and attended junior high and high school via Stanford Online High School.

"Like, how cool was that?" she says. “I fell in love with it.”

Thumbing through the Guinness Book of World Records, she was inspired to set a record as the youngest person to run a marathon on every continent. By the time she was 14, she had done just that, completing all seven with her mom running alongside her.

After her dad died of an aggressive form of prostate cancer, Vinecki, then 9 years old, founded Team Winter, a foundation for cancer research and awareness. She tied donations to her running races, raising more than $500,000.

Growing up in Michigan, Vinecki cultivated a competitive spirit by playing sports with her three brothers. She focused on downhill ski events in the winter and kids' triathlons and running races in the summer.

"One thing I've learned from my athletic career: What you put in is what you're going to get out. And the harder you work and the more prepared you feel, the better you're going to do," says Vinecki, who is a four-time World Cup gold medalist in freestyle aerial skiing and placed 15th in the 2022 Winter Olympics. "It's the same with law school."

Vinecki is a 2L at St. Mary's University School of Law's online JD program. It has not been easy to balance training for the 2026 Milan Cortina Olympics while living in Utah and attending the part-time online program based in San Antonio.

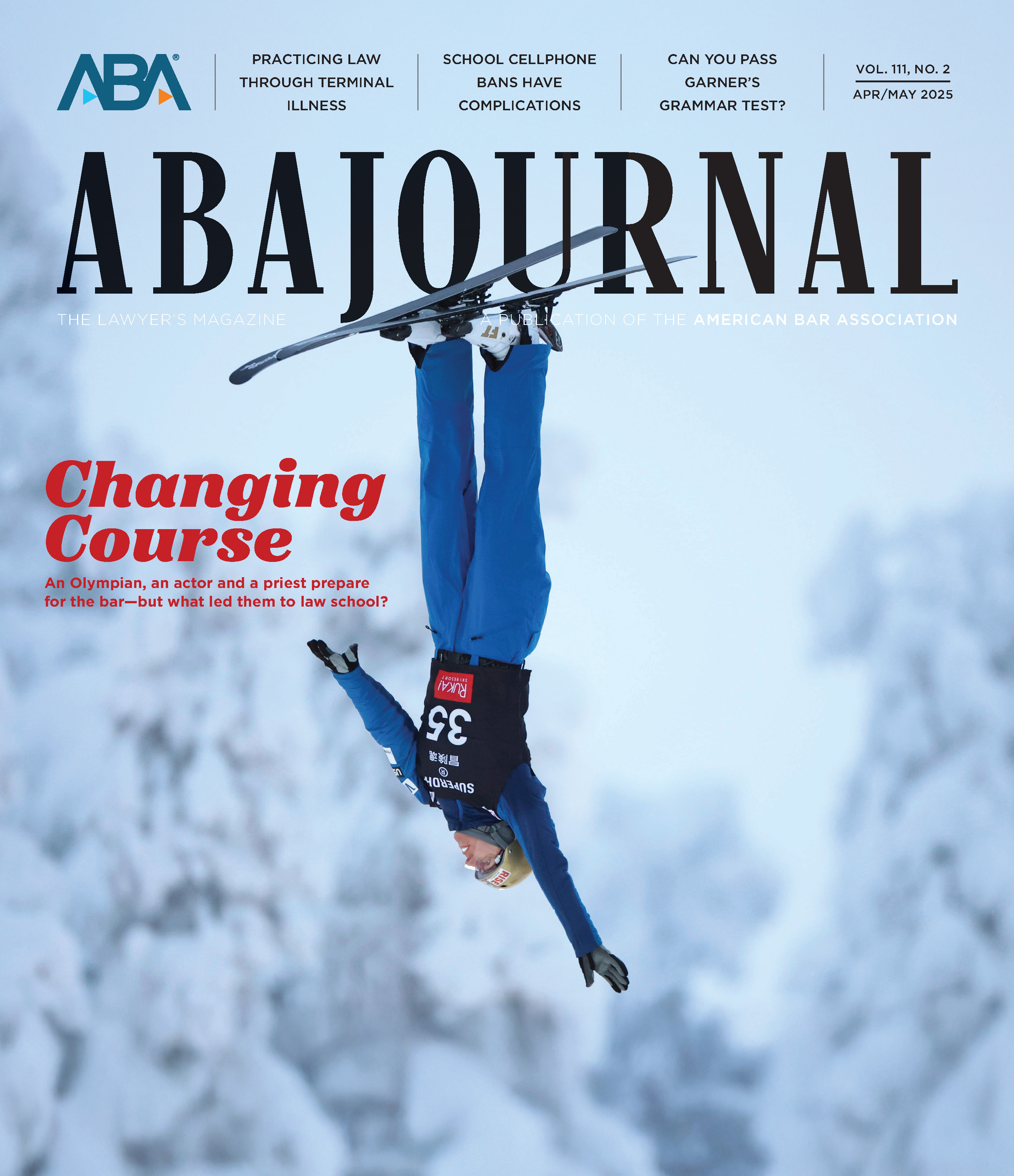

As a member of the U.S. Aerials Ski Team, Winter Vinecki takes flying leaps of faith every day, skiing down a mountain then launching herself off a ramp to perform twists and flips midair before landing on her feet. For her, the decision to add law school to her resumé was a relatively easy jump.

The ABA Journal talked with six law students and recent graduates with unusual first careers: Olympic athlete, flight attendant, behavioral analyst for kids with special needs, Catholic priest, Broadway actor and chimpanzee handler. While they had unique experiences before heading to law school, their backgrounds have impacted their studies and their hopes to effect lasting change in their original fields though law.

But some law students take very different paths.

These aren't the typical steps to law school that start late in high school–picking a college with a renowned political science program, overachieving in undergraduate school, taking the LSAT and ultimately getting into a solid JD program.

Hurling yourself into the air to flip and twirl while speeding down a mountain. Becoming ordained. Teaching animals how to socialize.

Mackenzie Freilich went from flying the friendly skies as a flight attendant to studying aviation law. (Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock)

He landed a job at PSA Airlines, a regional affiliate of American Airlines. "There's a big misconception that flight attendants only serve Cokes," he says. "We are the first responders of the sky. Being a flight attendant and learning the laws that go into the cabin portion of being on an airplane makes aviation safer for everybody every day." Freilich loved his job. But in February 2020, he left PSA, jumping at the chance to become trained in Dallas for the parent airline. Then, 4½ weeks into the six-week training, the program was suspended indefinitely as the coronavirus spread, drastically slowing demand for air travel–and new flight attendants. "I was crushed," he says. Eventually, he returned to PSA and was forced to undergo, once again, the regional carrier's required training. Unlike a lot of his classmates, he found studying the federal aviation regulations very exciting. "Learning the laws that go into the cabin portion of an airplane, I realized aviation law is constantly working to better safe and reliable transportation," he says. It got him thinking: "If I went to law school, I could do something that would make a difference, like shaping and honing regulations."

“There isn't really this clear path to follow, which brings some obvious challenges, but it also makes for an adventure.”

He applied to George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School, drawn to its courses on aviation law. Plus, he wanted to be near Washington, D.C., "where the laws are made," says the Rhode Island native who will graduate in May. While at the Arlington, Virginia-based law school, he founded the Air & Space Law Society and now serves as the American Bar Association law student liaison for the Forum on Air & Space Law. Last year, he interned at Collins Aerospace "and loved it," but he says he dreams of one day being an attorney for a major airline. Where he'll land after graduation "is kind of up in the air–no pun intended," he says. “There isn't really this clear path to follow, which brings some obvious challenges, but it also makes for an adventure.”

New behavior

After graduating with a bachelor's degree in business administration and management, Dana White was frustrated. She could not find a job in her targeted field–human resources–that paid more than $13 an hour. After a stint teaching business education in a high school, White was recruited for a job as a registered behavioral technician. The work involved going to the homes of children with autism to provide therapeutic services, ranging from identifying letters and numbers to helping them stop aggressive behaviors and self-injury. She found the work fulfilling and meaningful. To move ahead, White received her master's degree in behavior analysis, became a supervisor and a board-certified behavior analyst. But after working for several different service providers, she was stunned by the gaps in the industry's hiring standards as it struggled to fill the high demand for behavioral technicians. She says she saw many inappropriate candidates hired. One of her co-workers used illegal drugs before going to one child's home every day, White alleges, and another showed up at a family's home at 3 a.m. instead of 3 p.m., oblivious to the time and what the family needed. "I was appalled and traumatized by how there were no background checks," she says. White became upset when she learned of a new employee who wasn't informed of a child's peanut allergy and gave the child a Snickers candy bar. "The lack of regulations–it's scary," she adds. She wanted to make a real change, she says. "The traditional path would be to become a PhD or a PsyD," she adds, “but I saw the importance of the law.” Inspired, White entered Quinnipiac University School of Law's part-time program. She continues to work as a behavior analyst, handling a slightly reduced caseload. She anticipates graduating in 2026. "Law school has been the best decision," she says. "I didn't anticipate receiving so much support and guidance and mentorship." Because of her work, she has different skills than other law students, she says.

"I'm very open to how my path will unfold. But I do really hope that my experience and work will come together with law."

"I have gained a deeper understanding of why humans operate the way they do," she says. "I have a more refined skill set of interpersonal skills and expressing what I might want in a firm but respectful manner because I've had experience giving feedback to staff." In summer 2024, she put her background to good use as a legal intern at the Office of the Federal Defender for the District of Connecticut. Her supervisors were preparing for the sentencing of a client with autism who had committed a nonviolent crime. As they worked to avoid prison time for their client, they asked White to write a memo about standards in these types of cases. She could not find an instance of a court having to sentence an autistic defendant for a white-collar crime. "But even in cases of something as grave as child pornography, the courts did consider in their sentencing the autism diagnosis and the appropriateness of prison," White says. "That was a really more concrete way to help in these types of issues." Though she's accepted a full-time summer associate position at Wiggin and Dana in Connecticut, she's unclear on where she'll land after law school. "I'm very open to how my path will unfold," she says. “But I do really hope that my experience and work will come together with law.”

Divine inspiration

As he graduated from a seminary high school in Congo, Rodrigue Ntungu had a choice: Would he join the priesthood, or find another calling? Despite growing up in a religious family with ties to the Catholic church, he found the question to be not that simple. Ultimately, Ntungu became an ordained Jesuit priest and pursued multiple academic degrees and various converging professional pathways–teacher, magazine editor, author and currently a doctor of juridical science student at Georgetown Law, the first law school in the United States founded by a Jesuit higher learning institution. "All of us, we are basically multipotentialities. We combine many vocations in normal life," he says.

He then went on to study legal philosophy for an undergraduate degree at the Université Loyola du Congo in Kinshasa. There, he had his first interaction with the legal system while serving as the editor of a Jesuit community magazine. Ntungu's predecessor had published a photograph of a person without consent, and the offense required him to appear in a civil court case. "I had no idea about the court system, how it works, how to be an attorney," he says. As Ntungu watched the lawyers, he thought to himself, "I can do this." The case also exposed him to the corruption of the Congolese judiciary, which inspired him to want to change it. "Law became my second vocation," he says. Next, his Jesuit superiors encouraged him to attend Catholic University of Central Africa in Yaoundé, Cameroon, where he received a bachelor of law followed by a master's in business law with a focus on international investments law. His spiritual work influences his approach to the law. "The Jesuits are intellectuals," he says. "Taking care of others is also valid in the legal field." After graduation, he moved back to Congo to prepare to take the bar exam, which is held every two or three years, but it was delayed. "My Jesuit superiors decided that I should enroll at Hekima University College in Nairobi to pursue a master's of divinity," he says. While in Kenya, he continued researching investment law and published a book examining the Congolese legal system and capital mobility. On Jan. 3, 2016, he was ordained a Jesuit priest in Congo.

"When I discovered the Jesuits, I said to myself, 'Oh, I can teach while I'm a priest, and I can also be a minister to others.'"

"I can use the Jesuit identity to advance my legal career," he says. "It is a vocation within a vocation," both of which "fortunately make a person tidy and firm." Next, Ntungu headed to the University of San Francisco to attain an LLM in international transactions and comparative law in 2020. He then went to Georgetown Law for an LLM in international business and economic law before joining its SJD program, aiming to graduate in 2027. The program will help him advance his teaching career back home at his alma mater in Kinshasa. "It's more enriching to be researching and teaching. I'm more engaged when I'm creating knowledge and my students are learning from me how to advance the law," Ntungu says. “That's really my mission.”

Ready for his close up

As Dan Hoy was about to step in front of the off-Broadway footlights for the very first time, COVID-19 snuffed them out. He'd received his bachelor's degree in music theater from Baldwin-Wallace University's Conservatory of Performing Arts in 2018, and in early 2020, he was cast as an understudy in the off-Broadway debut of the musical Between the Lines. But the explosion of coronavirus cases that spring shut down rehearsals and led to the cancellation of the show's opening. "The first thing to go in the pandemic was live entertainment," he says. To stay afloat, he worked several different jobs, including as a tax administrator, a pharmacy technician and a summarization writer. "I realized if something happens again and acting work dries up, I'd have to find financial stability in something else I'm passionate about," he says. Inspired by his mother, Kelly Hoy, chief legal officer at Bellwether Enterprise Real Estate Capital in Cleveland, he took the LSAT in 2021. He was accepted to Syracuse University College of Law's hybrid online JD program, which requires short on-campus courses. But just as classes were to start, theaters reopened, and Between the Lines finally debuted. "That meant I wasn't able to then fulfill the residency requirement at Syracuse," he says, "so at that point, I shelved the idea of law school." But when that musical closed after three months, he again experienced the fragility of the economic life of an actor. He took a new look at online law schools and found Case Western Reserve University School of Law's fully online JD program, allowing him to attend school anywhere and on his own schedule. He is now a 1L. While law school differs greatly from a performing arts program, he finds his performance and creative training "to think outside of the box has been very, very beneficial at law school." The ability to think on his feet–a helpful skill when getting cold-called in class to argue a specific side of a case–"is something I developed through my creative education," he says. Since starting law school, he's performed in the company of Into the Woods at the Great Lakes Theater in his native Cleveland, then in Frozen at the Maltz Jupiter Theatre in Florida. During the demands of dress rehearsals and tech days, often requiring 10 to 12 hours of rehearsal, "I just bring my laptop and books to rehearsal," he says. "I do a few hours of studying before tech from the dressing room, get in costume, go on stage for a few hours. Take a dinner break, come right back onto my laptop, then right back in costume for a few hours." Once a show is open, things settle down, allowing more time for his studies, he says.

"I want to practice at the same time I am a performer."

This year, he returns to the New York stage as part of the ensemble and the understudy for the Pirate King in a revival of Pirates! The Penzance Musical at Roundabout on Broadway, which opens in April. "I rehearse 48 hours a week," he says. Coupled with a law school workload, "it's intense." Ultimately, Hoy is interested in representing artists "to make sure they are given a fair shake in contract negotiations" while continuing to be on stage himself. "I have friends who could have benefited from legal support. I want to give that support, but I want to practice at the same time I am a performer," he says.

Swinging toward advocacy

Amanda Reyes loved her job at Save the Chimps. Being a care technician at the Florida sanctuary for chimpanzees fulfilled her lifelong interest in working with animals. "I wanted to make sure I was doing my best so the chimps had the best day possible," she says. As a kid, Reyes wanted to become an American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals officer, inspired by a show on Animal Planet. When it was time for college, she pursued a bachelor's degree in biology at Salisbury University in Maryland while volunteering, then interning, at the local zoo. "You can't look at an animal and deny that they have feelings," she says. “They have sentience, and they have rights.”

Her own feelings grew after college when she worked as a research assistant at Duke University as part of its work supporting the Kalahari Meerkat Project looking at those animals' social bonds. "I did a lot of data collection for them, and I thought I wanted to get my PhD," she says. Ultimately, she backed away from academia and instead moved to Florida to return to animal caregiving. First, she worked at Jungle Friends Primate Sanctuary, managing the care of squirrel monkeys and brown capuchin monkeys, then she shifted to Save the Chimps in 2016. There, she worked with chimps, helping the make their veterinary checkups less stressful. Her favorite time with the animals was conducting "howdys," which is when chimps are introduced to each other. First, caregivers and staff discuss each animal's personality traits, then they play matchmaker for those chimps that seem compatible. Gradually, caregivers move the animals' enclosures closer to each other, eventually opening a connecting chute with a mesh separating them, allowing the chimps to choose to meet each other physically. The caregivers then watch their reactions. "It was exciting," she says. "We would constantly assess how they were doing." But she wanted more of a challenge. The logical career path was to become a manager at the sanctuary, but that moved her focus away from the animals. "That wasn't the step I really wanted to take," she says.

At the time, Freilich was an undergraduate majoring in paralegal studies at Roger Williams University and thought that maybe someday he'd go to law school. But the allure of free travel and his extroverted nature made working for an airline feel like a natural step away from that path.

While serving as a store manager for a Starbucks in Bristol, Rhode Island, one of Mackenzie Freilich's direct reports was also working as an airline flight attendant.

"Sports always will be a huge part of my life," she says, “but I want to be able to have a career that I can help people solve problems.”

After law school, she hopes to combine athletics and property management with law.

"They allowed me to take it at 6 or 7 p.m. instead, so I [still had a good shot] at doing well on the exam and not being dead asleep," she says.

The familiar flexibility of online classes suits her. During final exams in 2023, she was competing in Finland, and the test was scheduled for the middle of the night in Scandinavia.

Typically, her days are filled with school and training, but she is currently focused on recovering from a cervical disc herniation she suffered in February. "Of course, I eat and sleep sometimes in there as well," she adds.

Her mother discovered St. Mary's online program in 2022, and Vinecki applied. "It was just so neat because I'd been used to doing online schooling for years and years," she says.

"There's no way I could do in-person law school while still professionally skiing," she says. "I'm traveling many times for two months on end–sometimes more–throughout the winter."

At the University of Utah, Vinecki studied business administration, taking a mix of in-person and online classes while continuing to balance the demands of the U.S. Ski Team. A business law class "was right up my alley," she says, offering practical skills helpful for handling her real estate rental business and her sponsorship contracts. That sparked her interest in law school. But when she graduated in 2021, no accredited law schools offered fully online programs.

In the eighth grade, she moved away from her mom and brothers to Utah to train full time on the Fly Freestyle elite development team and attended junior high and high school via Stanford Online High School.

"Like, how cool was that?" she says. “I fell in love with it.”

Thumbing through the Guinness Book of World Records, she was inspired to set a record as the youngest person to run a marathon on every continent. By the time she was 14, she had done just that, completing all seven with her mom running alongside her.

After her dad died of an aggressive form of prostate cancer, Vinecki, then 9 years old, founded Team Winter, a foundation for cancer research and awareness. She tied donations to her running races, raising more than $500,000.

Growing up in Michigan, Vinecki cultivated a competitive spirit by playing sports with her three brothers. She focused on downhill ski events in the winter and kids' triathlons and running races in the summer.

"One thing I've learned from my athletic career: What you put in is what you're going to get out. And the harder you work and the more prepared you feel, the better you're going to do," says Vinecki, who is a four-time World Cup gold medalist in freestyle aerial skiing and placed 15th in the 2022 Winter Olympics. "It's the same with law school."

Vinecki is a 2L at St. Mary's University School of Law's online JD program. It has not been easy to balance training for the 2026 Milan Cortina Olympics while living in Utah and attending the part-time online program based in San Antonio.

As a member of the U.S. Aerials Ski Team, Winter Vinecki takes flying leaps of faith every day, skiing down a mountain then launching herself off a ramp to perform twists and flips midair before landing on her feet. For her, the decision to add law school to her resumé was a relatively easy jump.

The ABA Journal talked with six law students and recent graduates with unusual first careers: Olympic athlete, flight attendant, behavioral analyst for kids with special needs, Catholic priest, Broadway actor and chimpanzee handler. While they had unique experiences before heading to law school, their backgrounds have impacted their studies and their hopes to effect lasting change in their original fields though law.

But some law students take very different paths.

These aren't the typical steps to law school that start late in high school–picking a college with a renowned political science program, overachieving in undergraduate school, taking the LSAT and ultimately getting into a solid JD program.

Hurling yourself into the air to flip and twirl while speeding down a mountain. Becoming ordained. Teaching animals how to socialize.

Mackenzie Freilich went from flying the friendly skies as a flight attendant to studying aviation law. (Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock)

He landed a job at PSA Airlines, a regional affiliate of American Airlines. "There's a big misconception that flight attendants only serve Cokes," he says. "We are the first responders of the sky. Being a flight attendant and learning the laws that go into the cabin portion of being on an airplane makes aviation safer for everybody every day." Freilich loved his job. But in February 2020, he left PSA, jumping at the chance to become trained in Dallas for the parent airline. Then, 4½ weeks into the six-week training, the program was suspended indefinitely as the coronavirus spread, drastically slowing demand for air travel–and new flight attendants. "I was crushed," he says. Eventually, he returned to PSA and was forced to undergo, once again, the regional carrier's required training. Unlike a lot of his classmates, he found studying the federal aviation regulations very exciting. "Learning the laws that go into the cabin portion of an airplane, I realized aviation law is constantly working to better safe and reliable transportation," he says. It got him thinking: "If I went to law school, I could do something that would make a difference, like shaping and honing regulations."

“There isn't really this clear path to follow, which brings some obvious challenges, but it also makes for an adventure.”

He applied to George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School, drawn to its courses on aviation law. Plus, he wanted to be near Washington, D.C., "where the laws are made," says the Rhode Island native who will graduate in May. While at the Arlington, Virginia-based law school, he founded the Air & Space Law Society and now serves as the American Bar Association law student liaison for the Forum on Air & Space Law. Last year, he interned at Collins Aerospace "and loved it," but he says he dreams of one day being an attorney for a major airline. Where he'll land after graduation "is kind of up in the air–no pun intended," he says. “There isn't really this clear path to follow, which brings some obvious challenges, but it also makes for an adventure.”

New behavior

After graduating with a bachelor's degree in business administration and management, Dana White was frustrated. She could not find a job in her targeted field–human resources–that paid more than $13 an hour. After a stint teaching business education in a high school, White was recruited for a job as a registered behavioral technician. The work involved going to the homes of children with autism to provide therapeutic services, ranging from identifying letters and numbers to helping them stop aggressive behaviors and self-injury. She found the work fulfilling and meaningful. To move ahead, White received her master's degree in behavior analysis, became a supervisor and a board-certified behavior analyst. But after working for several different service providers, she was stunned by the gaps in the industry's hiring standards as it struggled to fill the high demand for behavioral technicians. She says she saw many inappropriate candidates hired. One of her co-workers used illegal drugs before going to one child's home every day, White alleges, and another showed up at a family's home at 3 a.m. instead of 3 p.m., oblivious to the time and what the family needed. "I was appalled and traumatized by how there were no background checks," she says. White became upset when she learned of a new employee who wasn't informed of a child's peanut allergy and gave the child a Snickers candy bar. "The lack of regulations–it's scary," she adds. She wanted to make a real change, she says. "The traditional path would be to become a PhD or a PsyD," she adds, “but I saw the importance of the law.” Inspired, White entered Quinnipiac University School of Law's part-time program. She continues to work as a behavior analyst, handling a slightly reduced caseload. She anticipates graduating in 2026. "Law school has been the best decision," she says. "I didn't anticipate receiving so much support and guidance and mentorship." Because of her work, she has different skills than other law students, she says.

"I'm very open to how my path will unfold. But I do really hope that my experience and work will come together with law."

"I have gained a deeper understanding of why humans operate the way they do," she says. "I have a more refined skill set of interpersonal skills and expressing what I might want in a firm but respectful manner because I've had experience giving feedback to staff." In summer 2024, she put her background to good use as a legal intern at the Office of the Federal Defender for the District of Connecticut. Her supervisors were preparing for the sentencing of a client with autism who had committed a nonviolent crime. As they worked to avoid prison time for their client, they asked White to write a memo about standards in these types of cases. She could not find an instance of a court having to sentence an autistic defendant for a white-collar crime. "But even in cases of something as grave as child pornography, the courts did consider in their sentencing the autism diagnosis and the appropriateness of prison," White says. "That was a really more concrete way to help in these types of issues." Though she's accepted a full-time summer associate position at Wiggin and Dana in Connecticut, she's unclear on where she'll land after law school. "I'm very open to how my path will unfold," she says. “But I do really hope that my experience and work will come together with law.”

Divine inspiration

As he graduated from a seminary high school in Congo, Rodrigue Ntungu had a choice: Would he join the priesthood, or find another calling? Despite growing up in a religious family with ties to the Catholic church, he found the question to be not that simple. Ultimately, Ntungu became an ordained Jesuit priest and pursued multiple academic degrees and various converging professional pathways–teacher, magazine editor, author and currently a doctor of juridical science student at Georgetown Law, the first law school in the United States founded by a Jesuit higher learning institution. "All of us, we are basically multipotentialities. We combine many vocations in normal life," he says.

He then went on to study legal philosophy for an undergraduate degree at the Université Loyola du Congo in Kinshasa. There, he had his first interaction with the legal system while serving as the editor of a Jesuit community magazine. Ntungu's predecessor had published a photograph of a person without consent, and the offense required him to appear in a civil court case. "I had no idea about the court system, how it works, how to be an attorney," he says. As Ntungu watched the lawyers, he thought to himself, "I can do this." The case also exposed him to the corruption of the Congolese judiciary, which inspired him to want to change it. "Law became my second vocation," he says. Next, his Jesuit superiors encouraged him to attend Catholic University of Central Africa in Yaoundé, Cameroon, where he received a bachelor of law followed by a master's in business law with a focus on international investments law. His spiritual work influences his approach to the law. "The Jesuits are intellectuals," he says. "Taking care of others is also valid in the legal field." After graduation, he moved back to Congo to prepare to take the bar exam, which is held every two or three years, but it was delayed. "My Jesuit superiors decided that I should enroll at Hekima University College in Nairobi to pursue a master's of divinity," he says. While in Kenya, he continued researching investment law and published a book examining the Congolese legal system and capital mobility. On Jan. 3, 2016, he was ordained a Jesuit priest in Congo.

"When I discovered the Jesuits, I said to myself, 'Oh, I can teach while I'm a priest, and I can also be a minister to others.'"

"I can use the Jesuit identity to advance my legal career," he says. "It is a vocation within a vocation," both of which "fortunately make a person tidy and firm." Next, Ntungu headed to the University of San Francisco to attain an LLM in international transactions and comparative law in 2020. He then went to Georgetown Law for an LLM in international business and economic law before joining its SJD program, aiming to graduate in 2027. The program will help him advance his teaching career back home at his alma mater in Kinshasa. "It's more enriching to be researching and teaching. I'm more engaged when I'm creating knowledge and my students are learning from me how to advance the law," Ntungu says. “That's really my mission.”

Ready for his close up

As Dan Hoy was about to step in front of the off-Broadway footlights for the very first time, COVID-19 snuffed them out. He'd received his bachelor's degree in music theater from Baldwin-Wallace University's Conservatory of Performing Arts in 2018, and in early 2020, he was cast as an understudy in the off-Broadway debut of the musical Between the Lines. But the explosion of coronavirus cases that spring shut down rehearsals and led to the cancellation of the show's opening. "The first thing to go in the pandemic was live entertainment," he says. To stay afloat, he worked several different jobs, including as a tax administrator, a pharmacy technician and a summarization writer. "I realized if something happens again and acting work dries up, I'd have to find financial stability in something else I'm passionate about," he says. Inspired by his mother, Kelly Hoy, chief legal officer at Bellwether Enterprise Real Estate Capital in Cleveland, he took the LSAT in 2021. He was accepted to Syracuse University College of Law's hybrid online JD program, which requires short on-campus courses. But just as classes were to start, theaters reopened, and Between the Lines finally debuted. "That meant I wasn't able to then fulfill the residency requirement at Syracuse," he says, "so at that point, I shelved the idea of law school." But when that musical closed after three months, he again experienced the fragility of the economic life of an actor. He took a new look at online law schools and found Case Western Reserve University School of Law's fully online JD program, allowing him to attend school anywhere and on his own schedule. He is now a 1L. While law school differs greatly from a performing arts program, he finds his performance and creative training "to think outside of the box has been very, very beneficial at law school." The ability to think on his feet–a helpful skill when getting cold-called in class to argue a specific side of a case–"is something I developed through my creative education," he says. Since starting law school, he's performed in the company of Into the Woods at the Great Lakes Theater in his native Cleveland, then in Frozen at the Maltz Jupiter Theatre in Florida. During the demands of dress rehearsals and tech days, often requiring 10 to 12 hours of rehearsal, "I just bring my laptop and books to rehearsal," he says. "I do a few hours of studying before tech from the dressing room, get in costume, go on stage for a few hours. Take a dinner break, come right back onto my laptop, then right back in costume for a few hours." Once a show is open, things settle down, allowing more time for his studies, he says.

"I want to practice at the same time I am a performer."

This year, he returns to the New York stage as part of the ensemble and the understudy for the Pirate King in a revival of Pirates! The Penzance Musical at Roundabout on Broadway, which opens in April. "I rehearse 48 hours a week," he says. Coupled with a law school workload, "it's intense." Ultimately, Hoy is interested in representing artists "to make sure they are given a fair shake in contract negotiations" while continuing to be on stage himself. "I have friends who could have benefited from legal support. I want to give that support, but I want to practice at the same time I am a performer," he says.

Swinging toward advocacy

Amanda Reyes loved her job at Save the Chimps. Being a care technician at the Florida sanctuary for chimpanzees fulfilled her lifelong interest in working with animals. "I wanted to make sure I was doing my best so the chimps had the best day possible," she says. As a kid, Reyes wanted to become an American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals officer, inspired by a show on Animal Planet. When it was time for college, she pursued a bachelor's degree in biology at Salisbury University in Maryland while volunteering, then interning, at the local zoo. "You can't look at an animal and deny that they have feelings," she says. “They have sentience, and they have rights.”

Her own feelings grew after college when she worked as a research assistant at Duke University as part of its work supporting the Kalahari Meerkat Project looking at those animals' social bonds. "I did a lot of data collection for them, and I thought I wanted to get my PhD," she says. Ultimately, she backed away from academia and instead moved to Florida to return to animal caregiving. First, she worked at Jungle Friends Primate Sanctuary, managing the care of squirrel monkeys and brown capuchin monkeys, then she shifted to Save the Chimps in 2016. There, she worked with chimps, helping the make their veterinary checkups less stressful. Her favorite time with the animals was conducting "howdys," which is when chimps are introduced to each other. First, caregivers and staff discuss each animal's personality traits, then they play matchmaker for those chimps that seem compatible. Gradually, caregivers move the animals' enclosures closer to each other, eventually opening a connecting chute with a mesh separating them, allowing the chimps to choose to meet each other physically. The caregivers then watch their reactions. "It was exciting," she says. "We would constantly assess how they were doing." But she wanted more of a challenge. The logical career path was to become a manager at the sanctuary, but that moved her focus away from the animals. "That wasn't the step I really wanted to take," she says.

Robert Jackson

Robert Jackson

Source of the news: Abajournal.com